Braid Mission

Blog

Responding to Charlottesville

This weekend, I was mostly at a loss as I watched from afar what was happening in Charlottesville.

Sickening news reports were balanced in my Facebook feed by photos of several of my seminary classmates who were there as part of the counter-protest. Wearing clergy collars, church robes, or just their everyday attire, they were there to serve as a witness that hate and discrimination are not actually endorsed by Christianity. Some of them shared stories, prayer requests, and (thankfully) updates on their safety.

Charlottesville is only a couple hours from where I went to seminary in Alexandria, and a day’s drive from my hometown in Tennessee, so at most other points in my life I could have jumped in the car and joined them. I could have taken a stand; I could have been present. Instead, I was very far away in California, feeling immobile and at a loss for words.

But yesterday I heard a story that stirred some hope in me, so I want to share that with you.

It’s the story of a person: his name was Jonathan Daniels, and he lost his life in 1965, at the age of 26, as a civil rights worker. Daniels was in seminary at the time, and he had left school for the semester to follow The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s call for clergy to come to Selma to be part of the movement.

In August of 1965, Daniels was part of a group protesting businesses in a small Alabama town that had been unfairly discriminating against African-Americans. The group was arrested and thrown in jail for six days. The protestors were surprised by suddenly being let out of jail, so they had to wait for someone to come pick them up.

As they were waiting, Daniels and three other people walked across the street to buy sodas. As they approached the small corner store, a sheriff’s deputy came out onto the porch. He was yelling threats and pointing his shotgun at Ruby Sales, a 17-year-old African-American young woman in their group. Without hesitation, Daniels stepped between Ruby and the man. He was killed instantly by the shot that followed.

At the time of his death, Dr. King said Daniels’ action was “one of the most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry.” Every year The Episcopal Church remembers Daniels on August 14, the day he and his fellow protestors were thrown in jail. He is acknowledged as a “saint” and martyr.

I can’t say what I would do in that moment. I don’t know what you do. I am not suggesting that we try to find out. What heartened me was his instinct.

Jonathan Daniels didn’t go to Alabama that summer to become a hero or a martyr or a saint. He went there to walk with and stand in solidarity with those who were suffering. Yes, he wanted to be part of a greater movement for civil rights, but in the ultimate moment, it came down to his instinct for relationship. It came down to one person whose life he considered so valuable that he did not hesitate to protect it with his own.

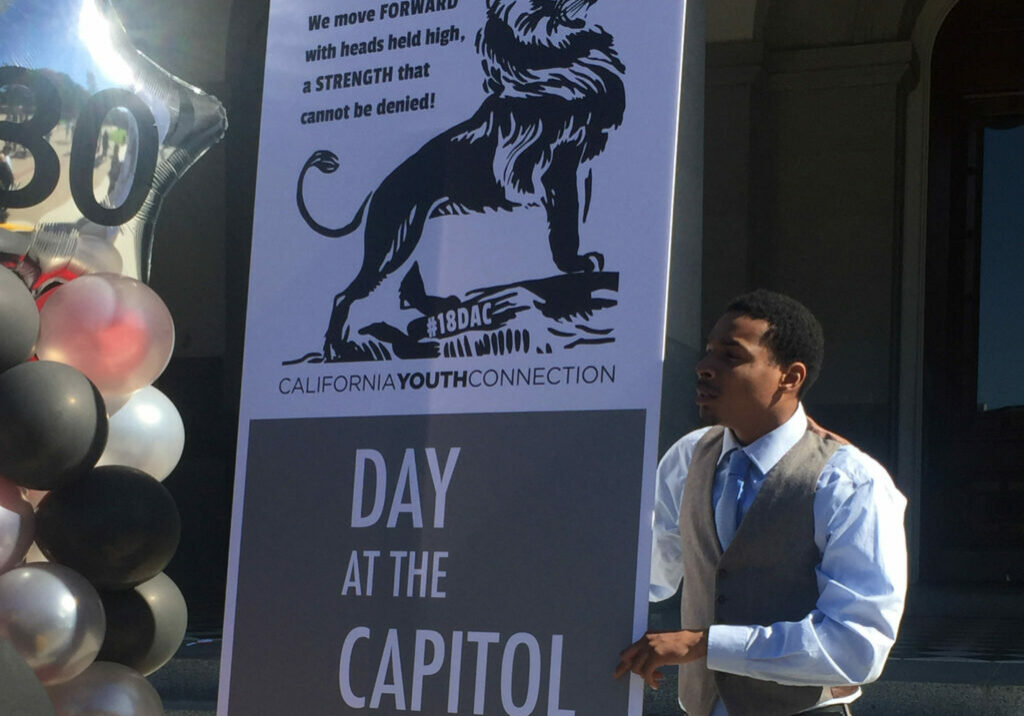

And so, when I heard this story again yesterday on Daniels’ annual “feast day,” I thought of all of our Braid mentors.

Not because – heaven forbid – any of them would ever have to literally take a bullet for the youth they mentor. But in some deep, metaphorical ways, that is what they do by walking in relationship with these young people.

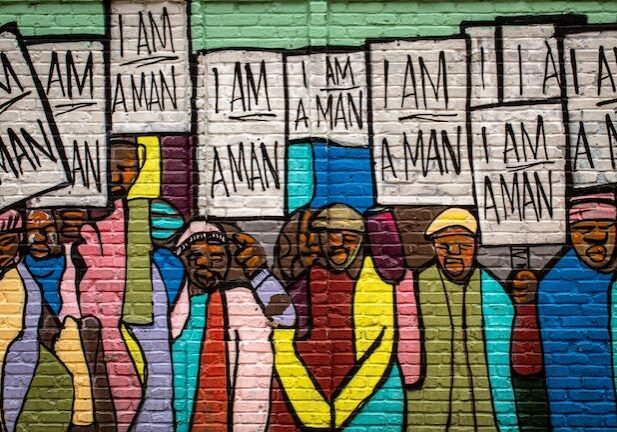

All of them became mentors because they wanted to help a young person who has been dealt a bad hand in life. And that bad hand goes far beyond the trauma of foster care. Charlottesville is another reminder that there are forces of this world that are always going to be threatening our youth, especially those of color. Foster care is deeply intertwined with systemic racism and poverty, and we will always be helping our youth stand up against those forces.

The beauty of Daniels’ martyrdom is that it was all worth it for him to save the life of one young woman who was the target of injustice. Not incidentally, that young woman grew up to be one of the great voices for civil rights over the last century, one of only 50 leaders individually featured in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

I know none of us were on the front lines in Charlottesville, putting our lives at physical risk. But I want to say again that the weekly commitment of mentors and facilitators is a deep and active form of social justice.

Reminding a young person of their worth and value as a human being, regardless of the burdens of their past or the color of their skin, is one of the most powerful gifts we can give to them and to the world.